Introduction to Pulmonary Embolism

This section introduces PE, its clinical presentation, risk assessment scores and diagnostic strategies

In this section:

Introduction

PE is a potential cardiovascular emergency caused by part of a thrombus, usually dislodged from a DVT (subsequently called an embolus), passing into the pulmonary circulation and preventing blood flow to the lungs

The pathway of a pulmonary embolus from the lower part of the body: inferior vena cava, to right atrium, to right ventricle, to the pulmonary artery. This might eventually obstruct blood flow to the lung. Patients with DVT are at risk of PE, a life-threatening event

Diagnosis

Signs and symptoms

PE is a potentially life-threatening condition, and in severe cases the occurrence of circulatory collapse and cardiac arrest may result in sudden death.

- Early fatality occurs in 34% of patients;4 therefore, rapid diagnosis is crucial

- The diagnosis of PE, however, may be missed because of its non-specific clinical symptoms

- Similar to DVT, PE is often asymptomatic,5 and approximately 30% of cases of PE are unprovoked (idiopathic)6,7

Common signs and symptoms of PE:4

- Dyspnoea

- Chest pain

- Haemoptysis

- Pre-syncope or syncope

Around 80% of patients with PE have signs of DVT, and approximately 50% of patients with proven proximal DVT have an associated PE.8

None of the above symptoms is specifically diagnostic of PE. The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines recommend the use of a stepwise diagnostic algorithm that:4

- Combines several evidence-based diagnostic strategies

- Stratifies patients according to their risk of early death based on clinical symptoms

- Has been validated in both the emergency ward and primary care settings

| Early mortality risk | Indicators of risk | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haemodynamic instabilitya | Clinical parameters of PE severity and/or comorbidity: PESI class III–V or sPESI ≥1 | RV dysfunction TTE or CTPA | Elevated cardiac troponin levelsb | |

| High | + | (+)c | + | (+) |

| Intermediate high | – | +d | + | + |

| Intermediate low | – | +d | One (or none) positive | |

| Low | – | – | - | Assessment optional; if assessed, both negative |

aOne of the following clinical presentations: cardiac arrest, obstructive shock or persistent hypotension. bElevation of further laboratory biomarkers, such as NT-proBNP or copeptin, may provide additional prognostic information. These markers have been validated in cohort studies but they have not yet been used to guide treatment decisions in randomized controlled trials. cHaemodynamic instability, combined with PE confirmation on CTPA and/or evidence of RV dysfunction on TTE, is sufficient to classify a patient into the high-risk PE category. In these cases, neither calculation of the PESI nor measurement of troponins or other cardiac biomarkers is necessary. dSigns of RV dysfunction on TTE (or CTPA) or elevated cardiac biomarker levels may be present, despite a calculated PESI score of I–II or an sPESI score of 0. Until the implications of such discrepancies for the management of PE are fully understood, these patients should be classified into the intermediate-risk category

High-risk PE is usually suspected if haemodynamic instability is present. Once stabilized, suspected ‘high-risk’ PE patients can undergo CT pulmonary angiography to confirm or dismiss the diagnosis of PE. If PE is not found to be the cause of haemodynamic instability, other causes should be investigated.6

Patients categorized as having ‘low-to-intermediate’ risk PE require further risk stratification using clinical judgement or a clinical prediction rule such as the Wells’ score.4,6

- If the clinical probability of PE is high, a confirmatory CT pulmonary angiography scan should be performed

- Patients with a ‘low/intermediate’ clinical probability of PE should undergo a D-dimer test before imaging

European Society of Cardiology algorithm for patients with suspected high-risk PE presenting with haemodynamic instability

Adapted from Konstantinides et al.4

aAncillary bedside imaging tests may include TEE, which may detect emboli in the pulmonary artery and its main branches; and bilateral venous CUS, which may confirm DVT and thus VTE. bIn the emergency situation of suspected high-risk PE, this refers mainly to a RV/LV diameter ratio >1.0. cIncludes the cases in which the patient’s condition is so critical that it only allows bedside diagnostic tests. In such cases, echocardiographic findings of RV dysfunction confirm high-risk PE and emergency reperfusion therapy is recommended.

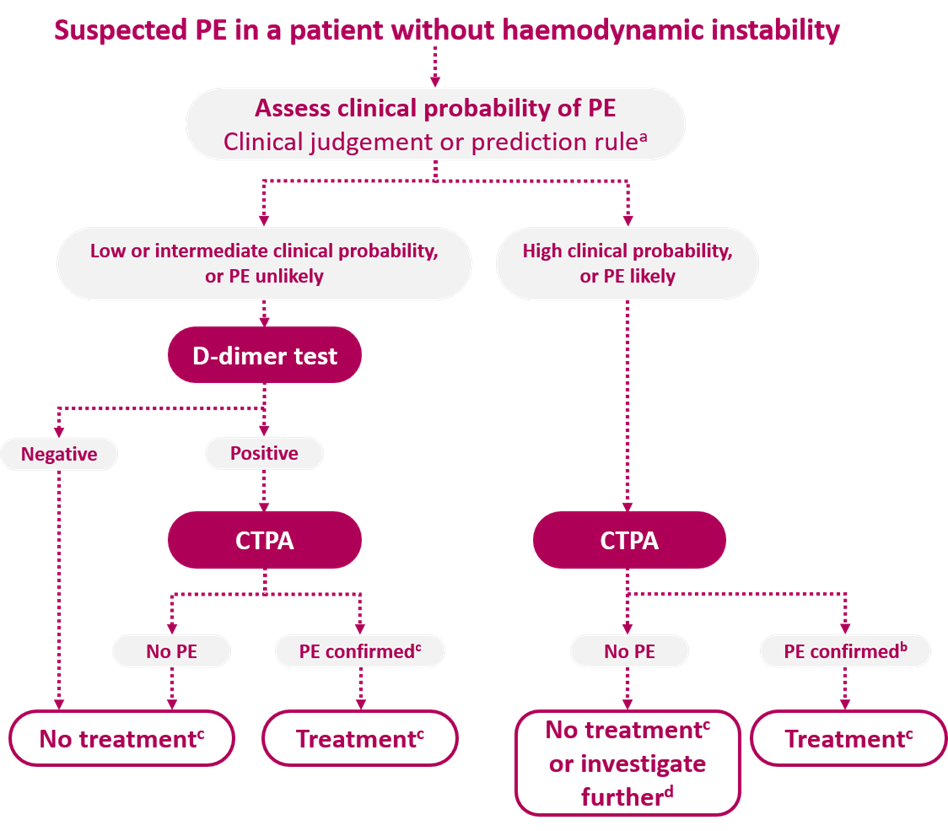

European Society of Cardiology algorithm for patients with suspected non-high-risk PE

Adapted from Konstantinides et al.4

aTwo alternative classification schemes may be used for clinical probability assessment, i.e. a three-level scheme (clinical probability defined as low, intermediate or high) or a two-level scheme (PE unlikely or PE likely). When using a moderately sensitive assay, D-dimer measurement should be restricted to patients with low clinical probability or a PE-unlikely classification, and highly sensitive assays may also be used in patients with intermediate clinical probability of PE due to a higher sensitivity and negative predictive value. Note that plasma D-dimer measurement is of limited use in suspected PE occurring in hospitalized patients. bCTPA is considered diagnostic of PE if it shows PE at the segmental or more proximal level. cTreatment refers to anticoagulation treatment for PE. dIn the case of negative CTPA in patients with high clinical probability, investigation by further imaging tests may be considered before withholding PE-specific treatment.

| Parameter | Score |

|---|---|

| Previous PE or DVT | 1.5 |

| Heart rate >100 bpm | 1.5 |

| Surgery or immobilization within the past 4 weeks | 1.5 |

| Haemoptysis | 1 |

| Active cancer | 1 |

| Clinical signs of DVT | 3 |

| Alternative diagnosis less likely than PE | 3 |

Patients with a high likelihood of PE should undergo diagnostic imaging. Those with a low/moderate likelihood should have a D-dimer test; if the latter is positive, imaging should be performed.4

Diagnostic imaging

CT pulmonary angiography is the preferred method of diagnostic imaging in patients with a clinical risk score indicative of PE because it is as accurate and less invasive compared with pulmonary angiography, the previous ‘gold standard’.

A V/Q scan is another established diagnostic test.4

- Exposes patients to significantly lower levels of radiation than CT pulmonary angiography

- Preferred in pregnant and young patients or those with severe renal impairment

- A V/Q scan indicating a high probability of PE provides sufficient evidence for the initiation of treatment but a low probability scan does not rule out PE – further diagnostic tests may be required

Further risk stratification in non-high-risk patients

In non-high-risk patients, further risk stratification is necessary once a PE diagnosis has been confirmed. The ESC guidelines recommend use of the PESI or sPESI score to further risk-stratify patients.4

- Intermediate-risk patients are identified as PESI Class III or higher or sPESI ≥1, and should be further stratified by assessment of right ventricular function and cardiac biomarker levels4

- Patients with either evidence of right ventricular dysfunction or elevated cardiac biomarkers are stratified as intermediate-low risk

- Patients with both evidence of right ventricular dysfunction and elevated cardiac biomarkers (especially elevated cardiac troponin levels) should be classified as intermediate-high risk

- Intermediate-high-risk patients should be monitored closely for clinical deterioration and may require rescue reperfusion therapy if haemodynamic decompensation occurs

The ESC guidelines recommend that low-risk patients should be considered for early discharge and home treatment providing proper outpatient care and anticoagulant treatment can be provided.

| Parameter | PESI | sPESI |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Points = age in years | If aged >80 years old = 1 point |

| Male sex | +10 points | – |

| Cancer | +30 points | 1 point |

| Chronic heart failure | +10 points | 1 point |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | +10 points | 1 point |

| Pulse rate ≥110 beats per minute | +20 points | 1 point |

| Systolic blood pressure <100 mmHg |

+30 points | 1 point |

| Respiratory rate >30 breaths/min |

+20 points | – |

| Temperature <36°C | +20 points | – |

| Altered mental status | +60 points | – |

| Arterial oxyhaemoglobin saturation <90% | +20 points | 1 point |

| Class I: ≤65 points Very low 30-day mortality risk (0–1.6%) Class II: 66–85 points Low mortality risk (1.7–3.5%) |

0 points = low risk Low 30-day mortality risk (1.0%) (95% CI 0–2.1%) |

|

| Class III: 86–105 points Moderate mortality risk (3.2–7.1%) Class IV: 106–125 points High mortality risk (4.0–11.4%) Class V: >125 points Very high mortality risk (10.0–24.5%) |

≥1 point(s) = not low risk 30-day mortality risk (10.9%) (95% CI 8.5–13.2%) |

CI, confidence interval

The 2018 British Thoracic Society (BTS) guidelines for outpatient management of PE, recommend treatment with either LMWH plus dabigatran or edoxaban, or a single NOAC (rivaroxaban or apixaban); with preference given to a single NOAC (rivaroxaban or apixaban) regimen to minimize potential confusion over dosing and administration. These guidelines also provide guidance on evaluating patients with PE for outpatient management.10

BTS guidelines for the identification of patients with PE suitable for outpatient management9

*Patients with cancer or those who are pregnant or within 6 weeks’ post-partum may be considered for outpatient management

References

- Geerts WH, Bergqvist D, Pineo GF et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (8th Edition). Chest 2008;133:381S–453S. Geerts WH, Bergqvist D, Pineo GF et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (8th Edition). Chest 2008;133:381S–453S. Return to content

- Pengo V, Lensing AWA, Prins MH et al. Incidence of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension after pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med 2004;350:2257–2264. Return to content

- Lang I. Advances in understanding the pathogenesis of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Br J Haematol 2010;149:478–483. Return to content

- Konstantinides SV, Meyer G, Becattini C et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Eur Heart J 2020;41:543–603 Return to content

- Girard P, Musset D, Parent F et al. High prevalence of detectable deep venous thrombosis in patients with acute pulmonary embolism. Chest 1999;116:903–908. Return to content

- Konstantinides SV, Torbicki A, Agnelli G et al. 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism. Eur Heart J 2014;35:3033–3069. Return to content

- Torbicki A, Perrier A, Konstantinides S et al. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolism of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2008;29:2276–2315. Return to content

- Tapson VF. Acute pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med 2008;358:1037–1052. Return to content

- Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M et al. Derivation of a simple clinical model to categorize patients probability of pulmonary embolism: increasing the models utility with the SimpliRED D-dimer. Thromb Haemost 2000;83:416–420. Return to content

- Howard L, Barden S, Condliffe R et al. British Thoracic Society guideline for the initial outpatient management of pulmonary embolism (PE). Thorax 2018;73:ii1–ii29. Return to content